Microbial biodiversity

A BIAM team has just revealed the diversity of bacteria that produce minerals composed of calcium carbonate inside their cells. This discovery could inspire innovative solutions for carbon capture or ecosystem preservation in the face of climate change, while inviting us to rethink the importance of these processes in natural environments.

Imagine microscopic organisms capable of manufacturing crystal- or stone-like materials inside their cells. This is exactly what some microorganisms do, like miniature craftsmen, through a process called biomineralization. This astonishing ability to produce minerals opens fascinating prospects for research, biotechnological applications and combating the effects of climate change.

Generally living on the seabed, in lakes or soils, these microorganisms use the elements available around them: metals, sulfur, carbon or oxygen, transforming them into solid minerals that they store inside their cells, to form a wide variety of biominerals. For example, certain Cyanobacteria (the first photosynthetic bacteria to produce oxygen) and Proteobacteria (a large branch of the bacterial kingdom) can form calcium carbonates, compounds similar to those found in oyster shells.

Until recently, the scientific community believed that only a few bacterial species living in specific aquatic habitats were capable of producing these solid minerals.

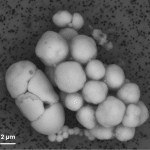

Scanning electron microscopy image showing several calcium carbonate-forming bacteria, in white. © karim Benzerara.

However, in an article published in The ISME Journal, recent BIAM PhD graduate Camille Mangin and her large consortium of collaborators from CEA, CNRS, Sorbonne University and IPGP, show that this ability is far more widespread. Their research brings to light an unsuspected diversity of bacteria capable of carrying out this fascinating process.

A key discovery in Lac Pavin

Caroline Monteil, project coordinator, explains: “Lac Pavin in Auvergne is a natural laboratory for BIAM. We’ve been conducting regular research there for the past ten years. Because of its volcanic origin, it has particular physical and geochemical properties that interest us in understanding the relationships between the functioning of microbial communities and their environment”. A few years ago, BIAM scientists revealed the existence of bacteria capable not only of producing amorphous (i.e. non-crystalline1) calcium carbonates, but also magnetite crystals, capable of interacting with the Earth’s magnetic fields. “At the time, we hadn’t yet measured the extent of the diversity of this group of bacteria, and we didn’t know the physiological and molecular mechanisms involved”, she adds. Since then, the researchers have deepened their knowledge of this group of bacteria, which could, in the future, be central to the development of bioremediation methods for radioelements.

Revealing microbial diversity with advanced tools

To better understand these biomineralization processes, and to be able to draw inspiration from them one day, the diversity of mineral-forming bacteria has been explored using a range of environmental microbiology, genomics and advanced mineralogy tools. “Over the last few years, our institute has developed cutting-edge expertise in the characterization of living organisms. These innovative techniques enable us to analyze microorganisms directly in their natural environment, without having to grow them in the laboratory”, adds Christopher Lefèvre, head of the BEAMM team behind the discovery. Techniques such as cryotomography and electron microscopy have enabled us to visualize and analyze in detail these mineral structures, which can represent up to 68% of their cell volume.

Implications for our understanding of life and ecosystem functioning

These observations raise many questions, particularly concerning the role of calcium carbonate, given its proportion, within bacteria and its impact on ecosystems.

By exploring the genomes of these microorganisms, BIAM and Génoscope researchers have shown that intracellular calcium carbonate formation is linked to CO2 fixation via distinct metabolic pathways. This shows that genetically very different organisms have therefore independently developed similar solutions for forming and storing calcium carbonate. “This indicates that this capacity is a key adaptation in oxygen-poor environments such as the sediments and water column of Lake Pavin”, emphasizes the researcher.

A new carbon sink?

This discovery opens up a new question: do these bacteria, by producing calcium carbonate, play a role in storing atmospheric CO₂ on an environmental scale? Scientists are now questioning their ability to act as long-term carbon sinks: “At this stage of our research, it remains to be determined whether these bacteria act as natural sinks by capturing the CO₂ present in their environment, or whether the calcium carbonates they produce store only the CO₂ derived from their own respiration.” As the study continues, BIAM scientists are exploring new directions. One thing is certain: these tiny builders still have many secrets to reveal.

1 In this case, the amorphous calcium carbonates produced by bacteria have no ordered crystalline structure. They appear in an unstable, unorganized form, often regarded as an intermediate stage before becoming well-defined crystals such as calcite or aragonite. This property is interesting because amorphous carbonates can have different chemical and physical characteristics from crystalline forms, which may influence their role in natural processes or their potential use in industrial applications.

Authors : Camille C. Mangin1, Karim Benzerara2, Marine Bergot1, Nicolas Menguy2, Béatrice Alonso1, Stéphanie Fouteau3, Raphaël Méheust3,

Daniel M. Chevrier1, Christian Godon1, Elsa Turrini1, Neha Mehta2, Arnaud Duverger2, Cynthia Travert2, Vincent Busigny4,

Elodie Duprat2, Romain Bolzoni1,2, Corinne Cruaud5, Eric Viollier6, Didier Jézéquel4,7, David Vallenet3, Christopher T. Lefèvre1,

Caroline L. Monteil1*

1Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, CEA, BIAM, UMR7265 Institut de Biosciences and Biotechnologies d’Aix-Marseille, Cadarache research centre, F-13115

Saint-Paul-lez-Durance, France

2Sorbonne Université, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, UMR CNRS 7590, Institut de Minéralogie, de Physique des Matériaux et de Cosmochimie (IMPMC),

4 Place Jussieu, 75005 Paris, France

3Génomique Métabolique, Genoscope, Institut François Jacob, CEA, CNRS, Univ Evry, Université Paris-Saclay, 91057 Evry, France

4Université Paris Cité, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CNRS, Paris F-75005, France

5Genoscope, Institut François Jacob, CEA, CNRS, Université Évry, Université Paris-Saclay, 91057 Evry, France

6Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement, LSCE–IPSL, CEA–CNRS–UVSQ–Université Paris-Saclay, 91198, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

7UMR CARRTEL, INRAE & Université Savoie Mont Blanc, Thonon-les-Bains 74200, France

*Corresponding author. Université Aix-Marseille, CNRS, CEA, UMR7265 Institut de Biosciences and Biotechnologies d’Aix-Marseille, CEA Cadarache,

Saint-Paul-lez-Durance F-13108, France. E-mail: caroline.monteil@cea.fr

Read more https://doi.org/10.1093/ismejo/wrae260